39 dolphins and whales had washed up dead on the beaches of the Indian Ocean Island of Mauritius by Friday 28 August. This was the third day running that dead dolphins had washed up after 18 were first discovered on Wednesday as numbers steadily rose since then.

The dolphin deaths came one day after the large front half of the Wakashio was deliberately and controversially sunk off Mauritius coast. Local journalist and human rights activist Reuben Pillay, who had chartered a boat, reported seeing many more dolphins, including juveniles, suffering just outside the lagoon close to the reported location of the sinking of the Japanese-owned iron-ore vessel.

This has triggered protests by the large Mauritian diaspora around the world, including a major march planned for Saturday 29 August, protesting against how the Government has handled the oil spill and subsequent clean up operations.

International developments around the Wakashio

In other developments around the world regarding the oil spill:

AUGUST 28 2020: Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announces resignation and walks after delivering … [+]

GETTY IMAGES

- The Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, has resigned today citing poor health. Japan’s longest-serving Prime Minister, he had aimed to build a public profile standing for greater ocean sustainability but had remained quiet about the oil slick and sinking of the large Japanese owned, but Panama flagged vessel. Japan has the world’s second-largest fleet of vessels in the world.

- The Prime Minister of Norway, Erna Solberg, who chairs the High-Level Panel on a Sustainable Ocean Economy, was pressured by WWF Norway on Friday on the actions that Norway or the High-Level Panel could take, as they had remained silent for the 35 days that the vessel had beached and then spilled oil along one of the world’s most unique biodiversity hotspots.

Mauritian diaspora around the world are organizing protests for Saturday 29 August 2020 in wake of … [+]

ALEX AUDIBERT

- This comes as international organizations such as Greenpeace have called on global shipping to end the use of fossil fuels in ships, following similar protests that Extinction Rebellion had staged earlier in the year against global shipping regulator, the IMO in March on the lack of ambition or independent oversight of global shipping’s commitment to higher climate and environmental standards.

Fears grow of an even more destructive cleanup operation in Mauritius

Volunteers collect leaked oil from the MV Wakashio bulk carrier that had run aground at the beach in … [+]

L’EXPRESS MAURICE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

All of these international developments occur as the preparations for the next phase of the oil clean up operation is considered. Concerns continue to be raised about the extreme secrecy in which the oil containment, salvage and now clean up are being conducted.

It is in part due to the secrecy that Mauritius finds itself in as much of a political crisis as an environmental one. Each decision during the cleanup and salvage operation had not been open to full international transparency which exacerbated the backlash when catastrophic failures occurred at every stage of the salvage and clean up operation, from the leaking of the oil, the ineffectiveness of the industry’s oil protection booms (requiring homemade booms to be created by an army of volunteers), the splitting of the vessel, and the deliberate sinking of the front section of the vessel within sight of the Mauritian Coastline at an undisclosed location.

Given this track record in the past month, strong fears are growing that the use of chemical dispersants in the cleanup operation along the once pristine beaches and mangroves of Mauritius could be even more destructive than the initial oil spill. Such chemical dispersants may visibly remove the oil – to make the beaches more palatable for tourists – but in doing so, only break down the oil into even smaller particles that would get absorbed by the smaller species along the coast (such as coral reefs). The use of these toxic chemicals would turn the Wakashio story from an oil spill disaster to one involving a deliberate toxic chemical spill, risking all life along the beaches and coral lagoons along the entire 30km stretch of beaches in Mauritius that have been ‘heavily affected’ according to the UN.

A worker with the Sourthern African National Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds cleans … [+]

GETTY

While these chemical dispersants may appear as harmless to humans as simple dishwater soap – chemical dispersants are often nothing more than low-grade industrial chemical detergents – the precise mechanism by which they break down the oil into smaller particles is exactly what makes them so toxic for corals that have been growing for over 10,000 years along the barrier reef of Mauritius and which are particularly sensitive to such chemicals. This would destroy the entire ocean and coastal microbiome where these chemicals are used (indeed it is the fine ocean bacteria around the reefs that give the reefs their color, and which would be wiped out with the use of chemical dispersants).

Without the transparency of the steps being taken for the cleanup operation for scientists to offer independent advice, there is fear that a chemical-led cleanup would be an order of magnitude more serious than the already bad oil spill – and would lead to permanent and irreversible damage to much of Mauritius’ South East and East coast, that depends on the barrier reef from coastal erosion due to the strong Easterly currents. This would be even more catastrophic to any form of rehabilitating tourism on the East Coast of Mauritius.

This would mean the news for decades later would not be about an ‘oil spill’ in Mauritius but more about the ‘chemical spill,’ where the cure was much worse than the initial disease.

Shrouded in Secrecy – 8 big questions

French Overseas Minister Sebastien Lecornu (L) and Mauritius’s Minister of Environment, Solid Waste … [+]

AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

While uncertainty rages around the secrecy of the cleanup operation, even the most basic questions have not been answered during since the grounding of the Wakashio and oil spill over the past 35 days. Here are eight big questions that remain unanswered, and which the international community is starting to demand answers.

These basic facts are foundational to any cleanup response, so the entire world is wondering why the secrecy, given the importance of these answers for any cleanup or rehabilitation response being planned.

1. How much oil was actually leaked into the coral lagoon?

This aerial picture taken on August 16, 2020, shows oil around the MV Wakashio bulk carrier that had … [+]

AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Incredibly as it sounds, the amount of oil leaked into the lagoon has not been disclosed publicly. 35 days after hitting the coral reefs and 22 days since oil started leaking, local citizens, independent scientists, NGOs, and the international community have been kept in the dark about a calculation so simple that even a high school maths student can calculate the answer. Here are the steps they would take (based on approaches in every bunker oil spill in recent history):

The vessel arrived in Mauritius with just over 1 million gallons of oil (sidenote: it remains unclear why the shipping company owner continues to use weight in metric tons to disclose information about the oil, when the volume is the standard measure and more relevant for oil spills than weight).

On 11 August, the last time a press release was made by the shipping company on the amount of oil leaked, they disclosed:

- 200,000 gallons had spilled into the lagoon

- 450,000 gallons still remained on the Wakashio

- 415,000 gallons had been pumped from the Wakashio onto a supporting tanker (most modern pumping equipment have gauges to track how much oil is flowing through).

Workers collect leaked oil at the beach in Riviere des Creoles on August 15, 2020, and these volumes … [+]

AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Since 11 August, the vessel then split in two on 15 August and oil could clearly be seen leaking from the vessel into the lagoon. The calculation that needs to be done is as follows:

- Total of 1,000,000 gallons of oil upon grounding on the reefs of Mauritius

- a) How much oil had been pumped from the vessel between 11 August and 15 August when the vessel split? This should be an easy calculation as the vessels were pumping directly from the Wakashio and there should be measures of how much the hold had been filled up (in volume).

- b) How much had been captured from the ocean? Again, drums of oil were being taken to an undisclosed decontamination site. These barrels would have had to be counted daily as they were loaded onto trucks and arrived at that site. This information has never been made public, but can easily be seen from photographs on the scene how easy it is to count the barrels and estimate the volume filled.

- c) How much is left in the ocean? Given that it is the winter months in the Southern Hemisphere, the ocean is cooler than normal, scientists can allow a generous 20% of this oil to have been evaporated into the atmosphere.

- d) The remainder is a very basic number – in gallons – of the oil left in the lagoon, beaches, and coastlines of Mauritius.

Venezuela’s protected Morrocoy National Park experienced a major bunker oil spill earlier in August … [+]

DE AGOSTINI VIA GETTY IMAGES

Even the US Embassy has acknowledged there may be a significantly higher amount of oil in the lagoon than the 200,000 gallons initially disclosed on 11 August. In a statement on the US Embassy’s website on 17 August offering the support and advice of the US Ocean Scientific Agency, NOAA, to the government of Mauritius, the estimated the spill could be between 210,000 and 300,000 gallons of oil – 50% greater than the initial disclosure on 11 August.

In Venezuela’s major oil spill in Morrocoy National Park at the start of the month, officials in the autocratic and highly secretive state initially refused to disclose the volume of the spill either. However, satellite analysis was able to perform various calculations based on the size of the spill to estimate that 26,730 barrels of oil (400,000 gallons) had been spilled into Venezuela’s pristine Morrocoy National Park.

2. What was the location that the Wakashio was sunk in?

24 August 2020: video and photography revealed the deliberate sinking of the Wakashio in bright blue … [+]

MOBILISATION NATIONALE WAKASHIO

Incredibly, despite 7 national press releases covering the towing operation between 19 August and the deliberate sinking on 24 August, the exact co-ordinates of the sinking have not been released by the Government of Mauritius. Neither the shipping company nor the IMO has responded to questions about the location, with the Japanese shipowner of the Wakashio, Nagashiki Shipping confirming in a statement to Forbes on 25 August that precise timing of the operation.

“At approximately 0030 hrs, local time on 19 August 2020, the forward section of the hull was successfully re-floated and towed offshore to an area designated by the authorities.

After that, they moved to the sea area designated by the Mauritius authorities to sink the hull and started work at 2100 hrs, local time, 21 August 2020.

At 1500 hrs, local time, 24 August 2020, the front part of the hull was submerged and allowed to sink in the designated sea area of Mauritian territorial waters, in accordance with the instructions of the authorities.”

3. Who authorized the sinking of the Wakashio?

French Overseas Minister Sebastien Lecornu (C) meets members of France’s Marine Nationale before … [+]

AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

A Government press release on 18 August implied that the French Experts brought over with the French Minister of Overseas Territories, Sébastien Lecornu, had advised on the location and decision to sink the vessel.

Despite several direct questions 8 days ago (since 21 August) to the IMO on the IMO’s role in the sinking and salvage operation, this role still remains surprisingly unclear. The IMO is the international shipping regulator that is also responsible for setting pollution laws under a set of international laws adopted in 1973, in reaction to a series of tanker accidents.

Yet it had sent a representative to Mauritius in an official capacity, whose mandate was very specific – focus only on the oil spill containment and response, and not the disposal of the vessels. This mandate was confirmed by an IMO spokesperson last week. For 8 days, journalists have been attempting to have transparency on the IMO’s role and responsibility given the implications that a major pollution event has occurred in front of the eyes of the world. The IMO has not responded to the specific question on their role in any advice to sink the Wakashio or the well established process that should have been followed for any deliberate decision to sink the vessel.

4. Where is the inventory of materials on the vessel before it was sunk?

21 August 2020: Footage of the operation to sink the Wakashio reveal the presence of an unidentified … [+]

MAURITIUS BROADCASTING CORPORATION

With 39 dead dolphins appearing along the coast of Mauritius the day after the sinking of the Wakashio, there has been consternation why hasn’t the materials of the Wakashio been disclosed to assist and scientific and cleanup operation. The secrecy is aggravating local efforts that are now scrambling the dark in the absence of such information

This is information that should be available from the shipowner at a click of a button. By not disclosing such information, this is compounding the complexity of the cleanup and response efforts.

Such disclosure should also include how much ballast water remained on board the vessel and where the origins of this ballast water came from.

Ballast water – which is often tens of thousands of gallons – is used to stabilize vessels, particularly when there is not full cargo on board – as was the case with the Wakashio. However, in recent years, it has been discovered that the transfer of ballast water from one part of the ocean to the other, is one of the biggest spreaders of ocean disease, bacteria and invasive species that may not belong in that part of the ocean.

New regulations came in force in 2017 to ensure much stricter regulation of the disposal of any ballast water. From the imagery of the operation around the Wakashio and the press releases, it was not clear whether there was any operation to pump out the ballast water and store this in a safe manner alongside the vessel.

5. What techniques or chemicals may be used in any cleanup of the oil spill along the beaches?

A crew cleans oil from the beach at Refugio State Beach on May 20, 2015 north of Goleta, California. … [+]

GETTY IMAGES

The very use of chemicals would be much worse than the oil spill itself. By not disclosing the chemicals being used, it is causing local and international scientists to grow concerned that such a clean up – which is in the interest of local Mauritians and the international community who are trying to preserve Mauritius’ unique biodiversity – is generating greater risk by keeping the international scientific community in the dark.

Press statements have revealed that the clean up operation has three main international advisers: ITOPF who have been brought in the main Japanese insurance firm for the Wakashio, and French clean up companies, Polyeco and Le Floch Depollution. However, the lack of public disclosure and accountability of these three organizations amid international concern on the state of the coral reefs given the high biodiversity sensitivity, is raising concerns about their liability in the event that a chemical pollution does even more harm than the original oil pollution.

Notably, in announcements by the Mauritius National Crisis Committee on 27 August, it was also revealed that critical biological samples were not being collected. This would have revealed the true extent and impact of the oil spill being present and detected in marine life around the lagoon.

Unmanned, autonomous scientific monitoring vessels such as Saildrone, could have allowed a much … [+]

SAILDRONE

Instead, the Government of Mauritius was opting for tests that would superficially indicate an immediate reduction of the oil leak (air and water quality testing only) and has not been international best practice for the past 15 years. Lessons from the 2007 Cosco Busan and 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill that US Ocean Agency, NOAA had been heavily involved with has revealed that it was only with biological testing that any impact of a major oil spill impact could truly be assessed. With the US Government offering the assistance of NOAA since 13 August and 35 days since the grounding of the ship and 22 days since oil started leaking, big questions will now need to be asked why the biological testing had not been carried out as more dolphins continue to wash up dead on Mauritius’ shores.

6. What has happened to independent scientific assessments?

MAY 21 2015: Independent scientists, such as SeaWorld Animal Care Specialist Gareth Potter, Dr. Todd … [+]

GETTY IMAGES

Despite the US Government offering the very best marine scientists and the French Minister of Outer Islands sent by President Macron to Mauritius, there has not been any real transparency on the sorts of biological sampling tests carried out in the country or the location of these including any autopsies of the 39 dead dolphins).

Videos of the sampling being taken by 6 Japanese specialists sent by the Government of Japan has been widely criticized online as this shows small scale snorkeling with underwater clipboards, whereas Mauritius could potentially have had access to fleets of autonomous surveillance vessel like Saildrone and others that are available to cover 100 times greater distances, with many more sensors and real-time imaging and machine learning identification layers of reef damage.

Why is the Japanese government not offering access to the state of the art science given the high biological sensitivity of the region where the accident occurred, the importance of a rapid response in those crucial early days after a major oil spill and now the fact over 39 dolphins and whales have washed up dead on the shores of Mauritius?

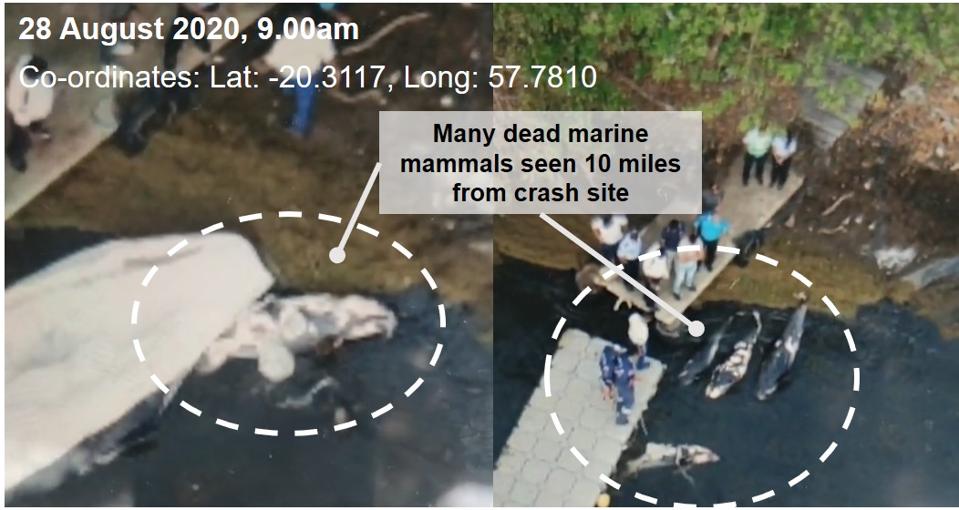

Drone footage taken by journalist and human rights activist, Reuben Pillay on 28 August, showed … [+]

REUBEN PILLAY

A press conference after the initial 18 dolphins washed up on Mauritian shored on Wednesday 26 August, was widely ridiculed, when the Mauritian Minister of Environment, a local whale-watching NGO, a whale tour boat captain and a specialist form the local aquaculture farm on the East Coast of Mauritius where dolphins had been loaded (as shown by local journalist Reuben Pillay), tried to question whether the deaths of the dolphins were anything to do with the major oil spill or sinking of the Wakashio in areas widely known to be important nursing grounds for such marine mammals in the region.

7. What is the impact of the engine fuel oil in the warm waters of Mauritius?

Extent of the spill can be seen from the air with the Wakashio at the top of the image taken on … [+]

AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Despite the UN regulator, the IMO authorizing the use of the VLSFO fuel being used in the Wakashio, in statements to Forbes last week, a spokesperson revealed that the IMO does not have any full understanding of the likely long term impact of this oil on humans and marine life.

On 19 August 2020, an IMO spokesperson said to Forbes, “because this fuel is so new, research has only just been initiated on its fate and behavior in the environment, particularly over a longer period. We know that some of the oil companies are financing research on this, and oil research centers e.g. CEDRE and SINTEF, have initiated work, but we don’t have any concrete information on this as yet, given the relative newness of these bunkers. In terms of the response related to the release of this fuel, it looks and behaves essentially the same as any other bunker fuel spill. It’s really the longer term fate and effects that are not yet known.” Bunkers are the fuel oil used by ships

This follows many studies from the 2007 Cosco Busan bunker fuel oil leak in the busy San Francisco bay that actually revealed that the bunker fuel oil (similar to what is being carried by the Wakashio) is more – not less – toxic than crude oil when exposed to high ultraviolet light of the tropics (where Mauritius is), and is being compounded by the cooler winter waters that keep this oil in the water for longer. This phenomenon – known as a heightened photo-toxicity due to UV light – has not been discussed by the shipping regulator, the IMO or the shipping company, raising even more questions about the safety of global shipping to have been allowing such dangerous fuels to be carried so close to biodiverse rich environments in more fragile single-hull vessels – which had been banned from Antarctica.

8. What was the cause of the accident? Call for independent international investigation led by G20.

Although captain of the Wakashio has been charged on August 18, 2020, it appears incredible that … [+]

L’EXPRESS MAURICE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

There are many rumors circulating across Mauritius around what the cause of the accident was, what information is being collected to ensure a transparent investigation, whether the voice recorder was intact, whether the vessel ‘black box’ recorder was also intact. Given the vessel had been on the reef for 12 days with a plan to refloat the vessel, all of this information should be available.

Amid growing fears locally of a cover-up given the strong interest of the Panama authorities – where the vessel was registered, the IMO – who are concerned about the fallout on global shipping of the accident, the Mauritius Government – who have been embarrassed by their response to the accident, and the shipping and insurance company – who fear one of shipping’s largest-ever payouts to rehabilitate this area, there have been strong calls for an independent investigation led by the G20, OECD or a team of credible international investigators to ensure the maximum transparency in such an investigation.

The important search for the truth

Local volunteers supporting the cleanup operation in South East Mauritius, following oil spill by … [+]

PHOTOGRAPHER: BEATA ALBERT (MAURITIUS 2020)

With the absence of a single point of truth in the country, the role of independent science is more critical than ever before.

This is not the first oil spill and the playbook and lesson from previous oil spills are very clear.

Why had such best practice procedures not been put into operation in Mauritius to build trust with the local community, when the oil and gas industry was already embattled with the climate crisis and significantly lower oil prices due to industry overproduction and the coronavirus pandemic?

Why has the global shipping and insurance industry not stepped in as moral actors to support a biodiversity hotspot, poor coastal fishing and tourism population, given this is the largest oil spill in the island nation’s history, and Mauritius is a country that had banned oil exploration in its waters for decades and the vessel concerned was not even supposed to be docking in Mauritius. It was a vessel that was using the moral authority of ‘innocent right of passage,’ yet did not adopt any responsibility for this passage.

This was not a shipping, oil or chemical incident of Mauritius’ doing, yet it is being forced to pay the social, environmental and economic costs.

The death of 39 dolphins over the course of Friday has shocked the nation and world. It is only with transparency and a shakeup in global shipping, can global shipping and insurance ever stand a chance of claiming any moral authority or trust again.

Forbes